Hello folks,

As the first quarter of 2025 ends, much is happening across various vectors, both locally and globally, that feeds into the background omni-war between the forces of totalitarianism and freedom.

It is for this reason, and the abject silence in Irish mainstream media on these matters, that I started FREE open public talks.

In our support group, we call it Ground Hurling!

The first of these had very high engagement.

It was held at the Radisson Hotel Little Island, Cork, on March 20th.

About 650 attended the Meet and Greet at 6pm.

The presentation ran from 7pm to past 9 pm, followed by Q&A, after which I stayed around to talk to anyone who came forward until 11 pm.

This is repeating at the City North Hotel off the M1 above Dublin Airport on Wednesday April 9th.

Please do come to support if you can, say hello to kindred spirits and build community.

There are no tickets required; entrance is free, and I’ll be there from 6pm.

Meanwhile, in response to what is now unfolding as Trump’s major tariff deadline approaches, I outline below a potential banana skin if the super-cooling of the US economy gives way to a combination of stagnant growth and rising inflation, known in the trade as Stagflation.

This is not a given, but it is serious enough to warrant a bulletin of its own.

Why it’s important is that it may hasten a tactical shift by Trump if his calculus starts to indicate an inbound recession greater and more damaging than the short and shallow type gamed out by his team in their tariff wars.

If that happens, the mood music may shift to a multilateral agreement to devalue the US dollar. Here’s my take on Stagflation.

Stagflation Risk: What Does It Mean and How Do I Position?

Our last bulletin on the Triffin Curse, I endeavoured to understand what is driving the Trump 2.0 administration, looking past the pearl-clutching, ad hominem attacks and barstool analysis from most of the Irish media.

In it, there is an argument that he applies tariffs as step one in a two-step process towards a multilateral international accord to devalue the US dollar and thereafter burden-share with the USA among its trading partners.

This is a knife-edge path; much has to come right because between gaming it and doing it right lies the potential for the ruination of his presidency.

Trump 2.0 is a rational actor with a specific agenda to avoid the USA’s sinking on its present course.

If it fails, we all do, which is why understanding US strategy and being prepared to burden-share is going to be important, no matter how much that means breaking bread together.

The Dark Host

Firstly, we need to revisit an old foe, Stagflation, this is stagnant economic growth, perhaps even negative growth, and inflation.

In this extended bulletin, I later outline the effect on asset classes of sustained Stagflation. This is not to say that Stagflation is inevitable, because it isn’t, but avoiding Stagflation whether short- or long-lived, now looks like it will be a near-run thing.

The combination of weakening data in the US and its uncertain White House helming is already noticeably spilling into consumer and corporate nerves about the tariffs.

This is having a chilling economic effect, but just how much will become clear over the coming months.

Financial markets, detecting the mood shift, are concerned enough to devalue companies most exposed to tariff wars.

There appears no doubt that US growth is peeling off fast, with forecasts for 2025 being downgraded across the board.

Whether this trajectory leads to recession, even if short and shallow, will remain unknown for some months, and bear in mind it is within the gift of Trump and the Fed’s cutting rates to provide relief.

Trump has to be extremely careful because even a short recession could take up to a year to claw out of, and that takes him into the mid-term elections, which means facing political backlash from unemployment rises, government workforce shrinkage and rising inflation.

The latter isn’t a given from tariffs because of offsets from dollar strength in external supply chains but it is probable, nonetheless.

The combination of growth in reverse, rising inflation and a Fed initially forced to cut rates to hold up employment is a toxic brew.

We know that driving this is the Triffin Curse, where deficits with trading partners desperate to hold US dollars eventually lead to insolvency.

Globalism, in addition to rising deficits now at post-WW2 levels in the developed world, has denuded the USA of much of its traditional industrial base.

However, some perspective is needed here, because its service sector is bigger and it has very successfully financialised its economy, giving investors a share of the action through Wall Street, far in excess of other countries.

Many times in these bulletins, the US virtuous circle of competitive advantage has been stressed, albeit at the price of a hugely unequal US society.

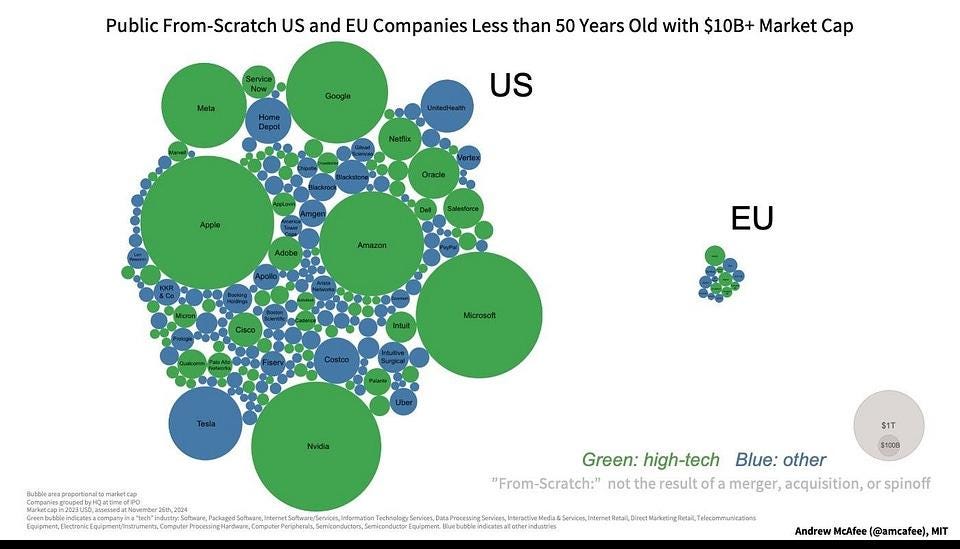

However, so we do not lose sight of its effects, below is a very sobering snapshot of the US enterprise pool and its equivalent for the EU, for companies worth more than $10bn.

The Draghi strategic report on the sclerotic EU ought to have bluntly stated that its chief USP is regulation.

The EU has a major task in reinventing itself if it is to compete with the US.

But US debt is on an unsustainable pathway, and Trump 2.0 knows that they have to take corrective action, otherwise the so-called bond vigilantes, who make money betting against nations’ credit, could visit the mothership, the USA.

This is no small matter, as the UK found out to its cost during the Truss lunge, a reckless move that could have caused a contagion in its financial system, pensions and gilts.

US debt servicing is eating up more and more of its revenues, equivalent to about 6% of its GDP, and shortly faces rolling over 7.5% of its bonds in credit markets as bonds mature. It is also running a $2 trillion deficit - the gap between its revenues and its expenditure.

The world’s second-largest economy, China, is in bad shape, as covered here many times.

It is ageing and struggling with a vast pool of internal debt linked to its development and reckless lending, and it is likely, it is thought, to follow the path of Japan after its destiny with excesses played out.

Europe is in better shape from a debt perspective, with France as the outlier, but has a growth problem, although Germany’s defence spending commitment and similar programmes across the EU will bring government-financed expansion.

It is also over-regulated to the point of strangling growth enterprises compared with the USA, despite its larger population and higher education.

Underneath all this are rising concerns of a bond heart attack moment causing a major player to restructure or default - that’s the Hollywood ending.

More likely is that eventually inflation will be unleashed to wipe off the excess burden by devaluing all fiat currencies and savaging bank deposits.

Remember, most excesses emanating from Central Bank extreme fiscal measures end up as someone’s asset; put together, this creates a net financial surplus, oodles of cash in banks, money markets and short-term bonds.

This is what bailed out Japan from collapse because its population was prepared to finance the burst Japanese Government with its savings.

Bond vigilantes hover over all the moves on the chess board and are now closely watching how aggressive tariffs are changing the calculus in favour of hammering a bond market to make vast fortunes, as George Soros famously did in 1992 against Sterling.

Gold’s Allure During Stagflation

Gold is still scorching.

Over the past year it has risen by more than 40% and is heading towards €3k per ounce; it had already breached this for the US Dollar at $3,024 by last Friday, March 28th.

Gold is widely regarded as a store of value which preserves purchasing power when inflation erodes the real value of paper currencies.

In Stagflation, where inflation is high and sustained, gold’s price typically rises as investors seek protection against currency devaluation.

The stagnant growth and the economic uncertainty that accompanies it heighten gold’s allure as a safe-haven asset.

Unlike equities or property, gold isn’t tied to corporate earnings or economic output, making it less vulnerable to the weak growth component of Stagflation.

It is why during periods of economic malaise and distrust in monetary policy, investors flock to gold.

The possibility of Stagflation and central bank purchases is now driving the price.

In Stagflation, the Fed and all Central Banks face a dilemma—raise rates to fight inflation or keep them low to stimulate growth?

Generally, in the past, rate hikes relative to inflation were modest.

Until a crisis point is reached, weak growth prevents hardening rates and thereby killing the economy’s capacity to expand above inflation.

Gold benefits because its lack of yield amid tepid rates is not deemed a drawback. In plainer terms, negative real rates, a feature of Stagflation, are a big tailwind for gold.

From 1971 to 1980, gold rose from about $35 per ounce to a peak of $850 in January 1980—a nominal increase of over 2,300%—driven by inflation spiking to double digits and economic stagnation.

Adjusted for inflation, gold’s real return above inflation was around 10% annually during that decade, vastly outpacing equities and fixed-income bonds.

But gold isn’t an all-weather asset; it can be volatile in Stagflation.

Price dips will occur, especially if investors liquidate assets for cash because of economic stress or if inflation expectations briefly soften. Gold’s long-term trend in Stagflation, however, is upward.

If Stagflation gives way to aggressive rate rises (less common but possible), gold’s lack of yield would hurt its relative appeal, but this risk is muted in sustained Stagflation, where growth worries temper rate increases.

In the 1970s, a weakening dollar amplified gold’s rise.

Gold is priced in US dollars, so its performance can also reflect dollar strength or weakness. If Stagflation weakens a major currency like the US dollar or euro, gold’s gains may be magnified for investors in those currencies.

In summary, gold shines in Stagflation as a defensive asset, historically delivering robust returns when inflation and uncertainty dominate.

Its performance makes it a compelling addition to a portfolio facing such conditions, though its volatility requires a balanced allocation, rather than an all-in bet.

Inflation-Linked Bonds: a Haven during Stagflation

Inflation-linked Government Bonds (Linkers), such as US Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) or UK Index-Linked Gilts, are designed to protect investors from inflation.

Their principal and interest payments adjust in line with CPI.

In a Stagflation scenario, Linkers tend to outperform fixed-interest bonds because their returns rise with inflation.

The real yield (adjusted for inflation) remains relatively stable, preserving purchasing power.

For example, if inflation is 5% and a Linker offers a real yield of 1%, the nominal return is 6%. In sustained high inflation, this adjustment mechanism makes Linkers a hedge against eroding value.

Fixed-interest bonds (eg traditional government or corporate bonds) suffer in this environment.

Their fixed coupon payments and principal lose real value as inflation rises, so, for example, if a bond pays a 2.5% coupon and inflation is 5.5%, the real return is -3%.

Inflation-linked bonds generally outperform fixed-interest bonds in Stagflation, because they mitigate the inflation risk that fixed bonds cannot escape.

Historical data, like the 1970s Stagflation period in the US, shows real assets or inflation-adjusted instruments held up better than nominal fixed-income securities.

Fixed-interest bonds suffer valuation falls as rates rise, resetting their attractiveness for new investment, and this acts as a buffer for the sector.

In Stagflation, however, where there is much uncertainty about the scale of inflation and the capacity of central banks to raise rates without triggering a sharp recession, linkers outperform because they surf the inflation wave no matter how high and long it is sustained.

Equities face a challenging environment in Stagflation because stagnant growth reduces corporate revenues and profits, especially for cyclical companies tied to economic expansion (eg, consumer discretionary, industrials).

Meanwhile, high inflation increases input costs (labour, materials), squeezing margins, unless firms can pass costs to consumers.

However, weak demand due to unemployment and low growth often limits pricing power.

Some equity sectors may fare better—energy and commodities often benefit from inflation, while defensive stocks (e.g. utilities, healthcare) may hold up due to stable demand.

Growth stocks, reliant on low interest rates and future earnings, tend to get thumped as inflation reduces the present value of future cash flows.

During the 1970s Stagflation, US equities (eg, S&P 500) experienced volatile but generally poor real returns, averaging around 1-2% annually after inflation, far below long-term averages of 8% to 10%.

Properties’ performance in Stagflation is a mixed bag, depending on how hard and deep Stagflation hits.

During Stagflation, property can act as an asset sink: housing is a tangible asset, often seen as an inflation hedge, but rising replacement costs (e.g. construction materials, labour) can boost property values.

Rental income may also rise with inflation, especially if leases include escalation clauses tied to CPI.

Commercial properties, on the other hand, with strong tenants can maintain cash flows.

When Stagnation hits hard, however, high unemployment and low growth reduce demand for housing and commercial space, increasing vacant space and capping rent increases.

If central banks raise rates to fight inflation, mortgage costs climb, depressing residential demand and property investments financed by debt.

This latter effect can often crater liquidity in property markets and amplify losses if forced sales occur.

So property can perform decently as an inflation hedge but is vulnerable to hard and deep stagnation. Houses in high-demand areas or inflation-adjusted leases fare better than over-borrowed property assets or investments in sub-prime property markets.

In summary, Linkers outperform fixed-interest bonds by maintaining real value; a strong choice in Stagflation especially if sustained.

Fixed-interest bonds underperform due to inflation eroding real returns and potential rate hikes.

Equity performance is generally weak, with low or negative real returns, though select sectors may buck the trend.

Property is a mixed bag—it offers inflation protection but is dragged down by hard stagnation; however, outcomes will depend on location, debt and lease conditions.

Gold is king in Stagflation but bear in mind that Stagflation is not yet a given based on what we see before us at the end of Q1 2025. In a sustained Stagflation environment, inflation-linked bonds also stand out as a safe haven compared to fixed-interest bonds, while equities and property face headwinds from the dual threats of stagnation and inflation.

Diversification across asset classes is always a must, but in Stagflation, a tactical tilt towards gold and inflation-linked bonds is a must.

Conclusion

That we are entering a Stagflation environment is not a given, but it is a rising risk.

It makes sense to hold on tightly to any gold and linkers that you may have and to consider adding to your position from your cash, as matters unfold over the coming months.

If you’d like to go into more detail or undertake an overall strategic review, you can contact my financial firm Hobbs Financial Practice Ltd at +353 (45) 409354 or eddie@eddiehobbs.com.

Until next time,

Eddie

Wow Eddie & Co. Well done. I salute 🫡 you. 650 people is massive.